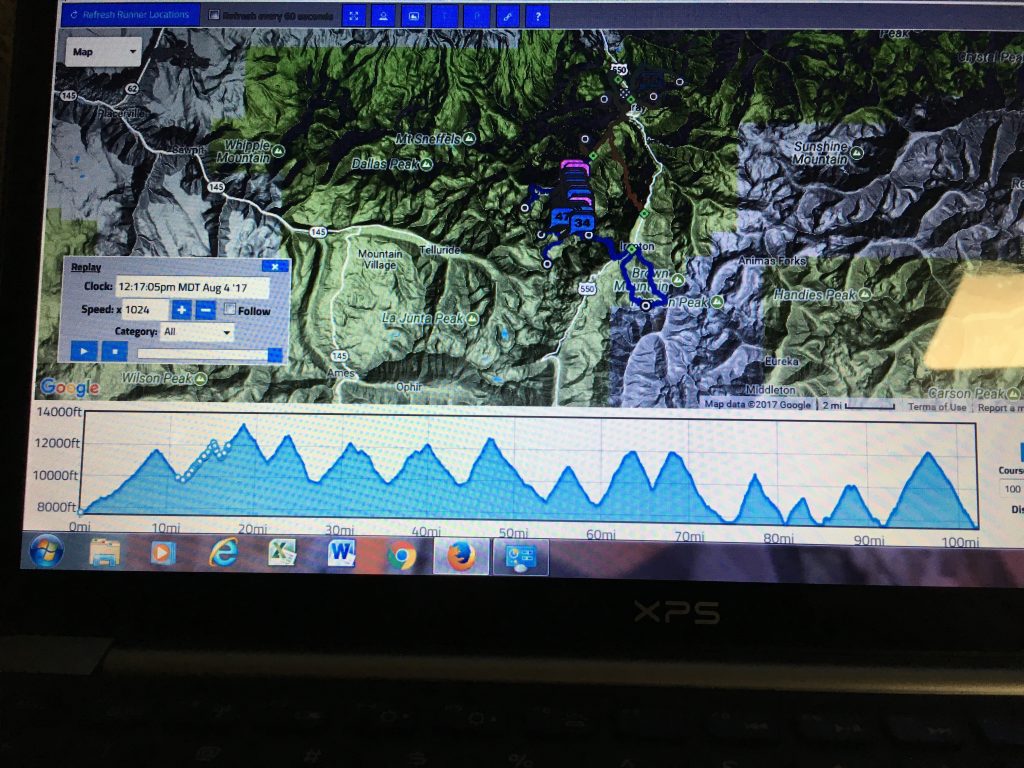

Several months ago over pizza and beer and far too much testosterone, my husband (Mike), our friend (another Mike, so I’ll call him Lamond hereafter), and our son Nick decided they’d all compete in 100-mile foot races this summer. As Mike and Lamond have completed the Leadville Trail 100 (LT 100) run several times already, they got online and without a lick of forethought, registered for the Ouray 100, a race with cumulative elevation gain exceeding a climb to the top of Mount Everest (41,862 ft gain, 83,724 ft change…see map below). No big deal, really, as they’re given 52 hours (nonstop but for an occasional aid station and tree watering) to complete the course. Buoyed by the enthusiasm of the older men, Nick registered for his first LT 100 run.

Lamond’s wife, Sunni, and I looked at one another through the haze of hormones and rolled our eyes. We have crewed many, many, far-too-many races over the years and knew that this one would be a humdinger.

I’ll interject a little tidbit here about my husband. Three days after he completed his ninth LT 100 Mountain Bike race a few years ago, he agreed it was time to undergo a full right hip replacement. Last year, three days after he completed his 11th one—because he had to earn the 1,100-mile jacket—he completed his transformation from Leadman to Titanium man with a matching left hip.

And one more tidbit about surgeons. When healing is complete and they say, “Sure! No restrictions,” they really should listen to what their patients tell them. Mike was quite clear with his surgeon about his desire to continue a life of mountaineering and racing.

“No problem. No restrictions,” said the doc. I could’ve punched him.

But enough tidbits. Back to the race.

Ouray, Colorado is a gorgeous location and we had trailer camped there three times prior to the event. Mike and Nick had hiked almost every leg of the race course, and Nick was prepared to pace Mike for the last 50 miles. Mike was motivated and confident in his ability to finish a race only 9 had finished the previous year.

“Get it out of your system,” he told the sniveling sky the night before the race as thunder boomed and lightning crackled through the atmosphere. It poured all night.

Race day started with partly cloudy skies. The soaking-pelting-brutalizing-hailing-rain began again within moments of the start of the race, but Mike had the right gear for every eventuality. A deluge would make completing this race just that much more badass.

Nick and Sunni and I would meet up with our racers that evening at a point where we’d see them three times between 4 p.m. and 3 a.m. the following morning. If they didn’t make the time cutoffs at each point, the race would be over.

Sitting with Sunni in our truck while Nick took my pink Victoria’s Secret umbrella to watch for our racers, I questioned my own sanity. The truck was packed with bags of gear and food and blankets—silly me, thinking I’d ever sleep!—and oh yes, Ranger, 90 pounds of muddy-wet German Shepherd.

“Here we are again.”

“Yup.”

“It’s stressful.”

“Waiting and worrying.”

“We keep supporting them, though.”

“Yeah. Maybe our two Mikes should live together next year—”

“And you and I should take a cruise!”

We were both pleasantly surprised when Lamond cleared the first checkpoint early, drenched, but in great humor. Nick and I stood under umbrellas while Sunni tended to his feet.

“So, what do you think?” he asked me. “Is it going to clear?”

I’d seen the forecast and paused for too long before looking him square in the eyes and declaring, “Yes.” He laughed out loud. Guess I didn’t really sell it, but he appreciated my optimism.

He took off for his first of two loops up the mountain at Ironton and we waited for Mike. And waited. And waited. I can’t help getting anxious when the wait stretches longer than planned. Both our men had told us they’d be okay if they’d given it their all but couldn’t make a time cutoff, and we almost believed them.

“Well, if Mike doesn’t make it in time, then Nick can pace your guy the last half.” I not-so-secretly hoped I wouldn’t have to spend all night in the muddy-wet-dog-smelly truck. Lamond had seen Mike earlier and said he was in good spirits, but his hip was giving him issues.

I was not happy. I was damp and hungry and worried. Nothing in the bags of not-quite-food appealed, and the idea of setting up our camp stove in the rain made me angry.

“I really hate this,” I confessed to Sunni. She understood completely.

Nearing the cutoff time, I saw the pink umbrella and Nick waving at us with a big smile, and behind him trudged Mike.

Shit, I thought. He made the cutoff.

He wolfed down a bowl of mac & cheese from the aid station, changed his gear for nighttime navigating, and off he went. As I watched my husband hobble up the mountain, I gave Nick a look that said, “Are you kidding me?”

“He’ll warm up. He always looks like that when he starts,” Nick reminded me. Nick always finds a way to say just the right thing to talk me down from my overblown worries, a skill he must have inherited from his father.

Lamond completed his first loop faster again than anticipated, and before he started off on his second loop, the moon peeked out.

“See! I told you it would clear!”

He thanked me for stopping the rain, but I knew it wouldn’t last. And it didn’t. Off he galloped up the mountain for lap two just as Mike completed lap one. Did I mention that Lamond is about six-foot-twelve and his walking stride is faster than Mike’s shuffling stride? No matter. Everyone was suffering.

Everyone but a racer I’ll call “Skippy Girl.” Skippy Girl skipped through every aid station throughout the race, and according to our guys, chatted the whole way too. It was enough to make a person want to hate her, but she was just so damned skippy that I really wanted to adopt her. I never offered, as it would’ve been weird—she being 29 and all—but the thought crossed my mind. Despite my miserable mental condition, she made me smile.

Lamond completed lap two at 10:20 p.m. just minutes after Mike started the lap (which took him four cold, dark, wet hours) and Sunni departed with Nick, leaving me in the rain with a stinky-wet-dog-wet-sock-smelling truck. Nick would go to the 58.8 mile point and wait for Mike with our friend Erich, who would start pacing Lamond at that point.

And now I must give praise to our pooch. We think Ranger is about 6 ½ (they said he was about 3 when we rescued him), and as long as he is with us, he’s a happy boy. I could learn a few things from him. Never once throughout that long night did he complain, despite being muddy and wet and crammed in among the bags of stuff in the back seat. He’s a very good boy.

I, on the other hand, grumbled and groused and tried to find a comfortable position while shaking from my mind thoughts of all the horrible things that could happen to my husband alone and impaired on a slippery mountainside. I knew he was hurting from the first time he limped into the checkpoint. And I knew he wouldn’t quit. I played Solitaire on my phone until my eyes blurred from weariness and ambient humidity.

Finally, a lone headlight lurched into sight at 2:14 a.m. Though I wanted to, I didn’t dare take a photo of Mike as he sat in the passenger seat, his hands frozen and barely able to scoop mac & cheese into his mouth, his stomach rejecting it immediately, his eyes a mixture of fatigue and resolve.

I wanted to say, “Stop. Please stop now.” But I couldn’t. I wouldn’t be the one to give him any reason to question his ability to complete this ridiculous race. And I knew I wouldn’t deter him from his goal even if I’d tried.

Instead, I kissed him and cheered him on to his next checkpoint, confident that once he reached Nick, he’d be in good hands. Calculating time to the next checkpoint I could go to, I wouldn’t see him again until around noon on day two of the race.

I returned to the trailer at about 3 a.m., took Ranger for a little walk since there was a break in the deluge, posted some Facebook updates, and threw myself under some covers on the bed.

At 8:45 a.m., almost 25 hours after the start of the race and 58.8 miles in, Mike missed the cutoff time where Nick was waiting.

“He’s done. Missed the cutoff. He’s in good spirits, though.” Nick’s text made me want to cry . . . from relief, because I knew the only reason Mike would stop would be because his titanium parts just weren’t working correctly, and from sadness, because I knew how strongly he wanted to finish this race.

His mind was far stronger than his matter this time.

“Thank you for supporting my insanity,” he told me when I picked him up. I told him he couldn’t get into bed without showering, and shortly after he was asleep, I got a text from Sunni:

When Mike [Lamond] came down to Crystal Lake he said he was done and had no desire to continue. He was easily talked into going back out for a nice strolling hike with his boys (both Erich and Nick went). Not sure if he’ll continue after the park. I told him ‘I’ll see you at the park and we can discuss you stopping.’ Figure mentally he’d be better saying he stopped at 75 miles. He now agrees how stupid this race is.

The next 24 hours blurred into a haze of back and forths to different checkpoints as Nick ran with Lamond throughout the day and night (day 2 was clear and moonlit!) to complete the stupid race by 8 a.m., a mere 48 hours after it had begun.

Sunni’s father played classic tunes on his bagpipes at the finish line, and nearly all of us complained of “something in the air” as we wiped our eyes. I secretly chastised myself for my meager discomforts. In fact, I felt great pride at the accomplishments of my husband, son, and friends who participated in the stupid 102.1-mile race.

Fifty-eight crazy people started the race and 22 strong, insane, skippy runners finished it. Many quit early on, and I can’t say I blame them. I was demoralized just standing under an umbrella. Many hadn’t trained enough to make the time cutoffs for each insane section of the race, and to those folks I say, “Good effort.” And some—like my mountain goat husband—gave more than they had to give.

What drives people to participate in these ultra-endurance races? Probably the same thing that drives people to compose music, to paint murals, to write books, to care for the sick and injured, to teach . . . it’s something in the genes and in the blood. We can’t help ourselves from pursuing our passions.

In less than two weeks, Nick will start the LT 100 run at 4 a.m. and I’ll be with him at the start. Mike and Lamond will be there to pace him for different sections the last 50 miles. And I’ll be there for him at the finish too, with tissues at the ready, just in case there’s “something in the air” again.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

If you like my writing, you might enjoy my books! Check them out here, and thank you!

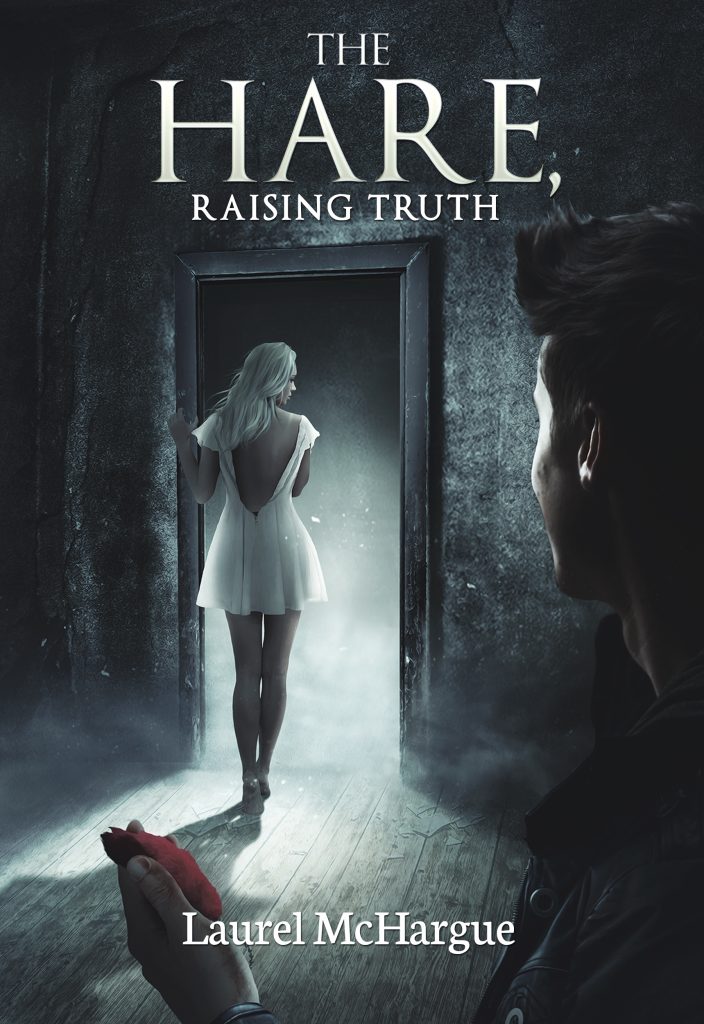

Many decades later and with 33+ years of marriage to the same guy, I’m pleased to say my luck has not run out. I’ll soon publish a novella called The Hare, Raising Truth about love and lust and lucky charms, and I’ve dedicated it to my husband. He is, truly, my lucky charm (oh, stop your gagging. It’s true). It’s a creepy story, but Mike said it’s my best writing yet. Yeah, he read it under sedation awaiting surgery, but I’m quite certain it didn’t affect his judgment at all. (read more for quick writing prompts about love!)

Many decades later and with 33+ years of marriage to the same guy, I’m pleased to say my luck has not run out. I’ll soon publish a novella called The Hare, Raising Truth about love and lust and lucky charms, and I’ve dedicated it to my husband. He is, truly, my lucky charm (oh, stop your gagging. It’s true). It’s a creepy story, but Mike said it’s my best writing yet. Yeah, he read it under sedation awaiting surgery, but I’m quite certain it didn’t affect his judgment at all. (read more for quick writing prompts about love!)